This is not the first time that Pentagram partner Natasha Jen has opened up a debate criticizing design thinking. Last year at 99u conf, she started a heated debate in which she called Design Thinking names such as “bullshit,” “jargon” and “extremely dangerous.” Very recently she gave another talk where she stuck to the same arguments and gave it another click-bait-esque headline. Again, through all of the controversy, she succeeded in her mission to start a discussion about Design Thinking. But just how successful was she?

Similarly, Thomas Wendt, who I’ve interviewed for The Pattern, raised concerns regarding the Human Centric Design (this time, without the media coverage).

I do agree with both of their discussions at certain points, but most of their points seemed to be pretty shallow. So, I started researching the topic myself. If both Design Thinking and HCD are overused buzzwords for what we do — then what are designers left with?

Design Thinking is an iterative process in which we seek to understand the user, challenge assumptions, and redefine problems in an attempt to identify alternative strategies and solutions that might not be instantly apparent with our initial level of understanding.

Many responses to Jen’s critique were from people teaching DT for a living. To make my point clear from the beginning: I’m advocating neither for or against Design Thinking, I simply want to explore the topic. I’m an advocate of critical thinking. This article is written with the aim to debunk false beliefs and to find answers to some questions that have been open for a long time.

#designthinking #people #innovative #workingtogether

#designthinking #people #innovative #workingtogether

What are the problems with Design Thinking?

According to Jen, the problem starts with the intangibility of the term itself. She sees it as a buzz-phrase — A danger. In her own words: it’s an outrageous, overly simplistic concept that she doesn’t understand.

Jen also has concerns about the process of acquiring Design Thinking knowledge. She claims that she has seen such courses for as little as £2.99. This is a threat not only to the design industry but to education as a whole, she said.

Moreover, she doesn’t consider post-its acceptable evidence for “real” design work. Jen’s openly ridiculing the vague, meaningless vocabulary used by advocates of Design Thinking and the generic formula applied to any “problem.”

Coming from a different perspective, Wendt too agrees with her on this point, saying that: “It’s a mistake to use just one methodology — in this case, HCD — and apply it as one-cure-for-all-projects-we-do.”

Myth #1: DT is thinking

Technically, Design Thinking is “thinking.” In practice this cycle of Inspiration, Ideation and Implementation is a solutions-based approach to solving customer problems.

By the words of Tim Brown, the CEO of IDEO and the author of Design Thinking methodology:

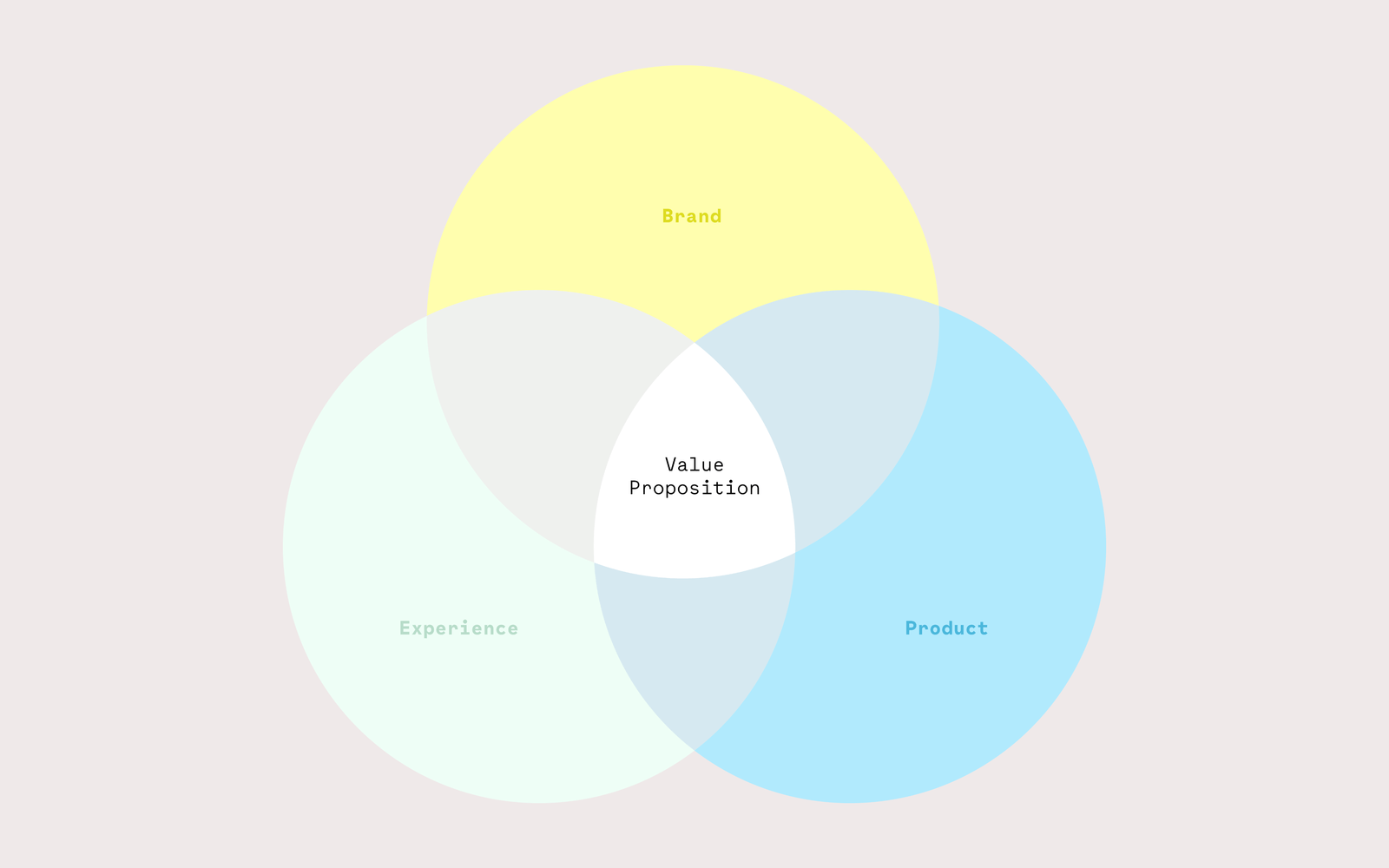

“Design thinking is a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.”

However, seeing Design Thinking as a ‘tool’ rather than thinking, offers a mechanism for organizations to explore the problem from the user’s perspective. That’s why the core idea behind Design Thinking is to empathize with the person we are designing for. Commercial teams are hard-wired to look at numbers and results, but can easily lose sight of that human element.

I see Design Thinking as a way to help them stay on track, combining what people want with what’s technologically feasible and economically viable. The simplicity of this method allows almost everyone to participate in the process and see the bigger picture.

Myth #2: If you skip one step or another, you’re not really “design thinking.”

From my experience (and literature backs me here), five stages of the Design Thinking process are not always sequential; they do not have to follow any specific order. Given that, you should not understand the phases as a hierarchal or step-by-step process. Instead, you should look at it as an overview of the modes or stages that contribute to an innovative project, rather than sequential steps.

Every project is different, just as each client’s challenges are different. Maybe I’m biased by my agenda, but it’s tough to think of a design practitioner that would not adjust the process accordingly.

It’s important to be mindful — whatever your process is.

Myth #3: It’s the best tool for every challenge

Both Jen and Wendt addressed this false belief: Design Thinking is not the best method for each problem you’re trying to solve.

Design Thinking is the norm, most of the time, when dealing with physical products that are tactile and it gives out the same experience to any user. It makes sense for a large company, particularly when a new product requires significant investments in engineering. For example, when developing the most optimal posture for a chair where the prime focus is on design, Design Thinking is certainly required.

On the other hand, HCD, as a subset of Design Thinking, is most used for experiences. This includes experiences such as UI/UX, a sales process, a payment process, a new methodology of farming, and many more that have multiple users and touch points that vary in experience from one user to the other.

So…?

However entertaining, Jen’s anecdotal evidence for her arguments are not making her claims any stronger. It does raise questions. I agree — it has been adopted as a buzzword by every consultancy and, frankly. Most companies seem to not truly understand it. It might look like as a rigorous one-size-fits-all method or random series of steps that must have been followed exactly, but that doesn’t mean IDEO’s original concept is not valuable.

Sharing the view of Spring co-founder, it’s rather elitist and counterintuitive to say that only designers should understand Design Thinking. Our industry is notoriously bad at articulating its value to the wider “non-design” world. If a fashionable buzz-phrase is all it takes to understand the value of design for the business, then I’m all for it. The more mainstream the understood value of our processes becomes, the better.

But, let’s say we put the Design Thinking (or Human Centric-Design for that matter) to one side. What are we left with?

A call for holistic solutions

A holistic design seems to be “the” alternative to centristic frameworks. It’s an approach which sees design as an interconnected whole that is part of the larger world. Holistic design promises to incorporate all aspects of the ecosystem. Its focus goes beyond users to the context on which it is dependent.

Currently, it’s mostly seen in architecture where it enables architects to account for the complexity. They examine the way that the design will appear aesthetically — in context. They’ll look at surroundings, consider the lighting during the day. Encompass the message of the project or practical things like how long will the structure last or how to reduce energy consumption.

Well, you may ask: “If a holistic design is this great, why is it not used instead of DT or HCD?” or “Why are there very few examples of successfully incorporated holistic solutions?”

Perhaps we’re just not used to thinking in the bigger picture because usually there’s no demand for it. Personally, I feel like one of its most significant issues is the intangibility of the framework itself. It’s like writing a sci-fi novel — it demands its practitioners to think about the distant future and must account for a lot of variables.

I’m not saying it’s impossible, but with all of our biases and flaws in thinking. It seems that our hands so far make the best holistic thinker — artificial intelligence.

What should designers do?

If there’s one takeaway, I think it’s that we should all remember to be more critical. Our industry still seems to undervalue the importance of questioning the processes and the tools we’re using. Examining broad spread methodologies is vital to any industry — progress is only possible through open discussion and through battling ideas.